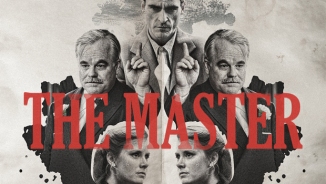

IT IS EERIE and discomfiting to have first viewed ‘The Master’ on the eve of Phillip Seymour Hoffman’s death. To have watched him fully embody the film’s title and seen his messianic command take shape and grow amongst his flock, even as it fractured at the foundations. To have been captivated, unblinking, by his rapport with Joaquin Phoenix—one ruddy, round, and relentless, the other wretched and wracked—in a connection ineffable and inexplicable to everyone but themselves. And above all to have thought, ‘This is a great talent. A gifted, grounded, and uniquely human performer. One who has grown alongside a director of equal merit, Paul Thomas Anderson, who recognizes and celebrates his gifts. What a rare prize it will be to watch them explore their potential together in the coming decades.’

IT IS EERIE and discomfiting to have first viewed ‘The Master’ on the eve of Phillip Seymour Hoffman’s death. To have watched him fully embody the film’s title and seen his messianic command take shape and grow amongst his flock, even as it fractured at the foundations. To have been captivated, unblinking, by his rapport with Joaquin Phoenix—one ruddy, round, and relentless, the other wretched and wracked—in a connection ineffable and inexplicable to everyone but themselves. And above all to have thought, ‘This is a great talent. A gifted, grounded, and uniquely human performer. One who has grown alongside a director of equal merit, Paul Thomas Anderson, who recognizes and celebrates his gifts. What a rare prize it will be to watch them explore their potential together in the coming decades.’

And now all too rare. There is a temptation to lionize a body of work once its creator is gone, not least when he left his career at its zenith. But ‘The Master’ was a compelling and memorable mystery even before news of Hoffman’s death broke, and it remains so in the aftermath, due in part to Hoffman’s presence but not wholly. Fraught subtexts and unresolved threads are unavoidable in any film that (allegedly) depicts the origins of Scientology and its founder, L. Ron Hubbard. And Anderson explores them like no one else.

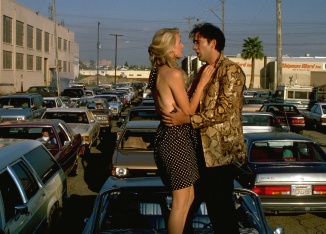

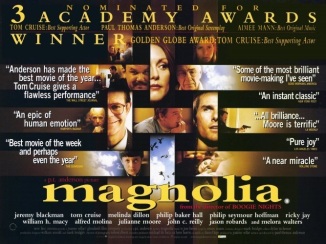

Anderson’s earlier films were expansive ensemble works, starting with ‘Hard Eight’ ‘Boogie Nights’, and culminating in the epic ‘Magnolia’. More recently he has narrowed and intensified his focus, first in the clunky but compelling ‘Punch Drunk Love’ (2003) before stunning audiences with ‘There Will Be Blood’ (2007). The leading actors in those films could not have come from more different traditions. The first, Adam Sandler: a crass, lumpy, deliberately amateurish everyman with a dismissible mien but hidden wounds. The second, Daniel Day Lewis: noble bearing, hard-cut profile, vast presence, smoldering emotions, and Shakespearean gravitas.

Anderson’s earlier films were expansive ensemble works, starting with ‘Hard Eight’ ‘Boogie Nights’, and culminating in the epic ‘Magnolia’. More recently he has narrowed and intensified his focus, first in the clunky but compelling ‘Punch Drunk Love’ (2003) before stunning audiences with ‘There Will Be Blood’ (2007). The leading actors in those films could not have come from more different traditions. The first, Adam Sandler: a crass, lumpy, deliberately amateurish everyman with a dismissible mien but hidden wounds. The second, Daniel Day Lewis: noble bearing, hard-cut profile, vast presence, smoldering emotions, and Shakespearean gravitas.

Five years later (the longest quiet stretch of Anderson’s career), Hoffman stepped forward to bridge the gap as the eponymous Master, called Lancaster Dodd. His creased face carries all the scorn and poise and confidence of a prophet, but still there is a boyish simplicity to his smile and common cast to his features that cuts through all cinematic artifice. How could he possibly be pretending? Acting at all? How could we not believe him? And collared by his side is Freddie Quell (Phoenix), an irrepressible alcoholic and hedonic WWII vet with PTSD who serves as the audience’s inlet to the Master’s private crusade. Virgil leading a pitiful Dante. In this role Phoenix is everything Hoffman is not—hunched while the other walks erect, ambivalent while the other is resolute, aimless while the other speeds upon a motorcycle towards a distant point across desert flats, laughing and helmetless. Quell is a piece of prey rolling over on the altar of its predator.

Both actors’ performances are transformative, so perfectly dissimilar as to create a seamless whole. It is not explained to us how they meet nor do they seem to know themselves (for a time). It is a relationship that simply exists because it must, and it does so more deeply than any other on screen. Thomas’s direction exploits the dynamic through his characteristically long takes, probing close-ups (echoing Quell’s job as a portraitist in the years after the war), and with such a shallow depth of field that two characters hunched over a table become floating heads of perfect focus amidst a wide sky of muddled stars.

Both actors’ performances are transformative, so perfectly dissimilar as to create a seamless whole. It is not explained to us how they meet nor do they seem to know themselves (for a time). It is a relationship that simply exists because it must, and it does so more deeply than any other on screen. Thomas’s direction exploits the dynamic through his characteristically long takes, probing close-ups (echoing Quell’s job as a portraitist in the years after the war), and with such a shallow depth of field that two characters hunched over a table become floating heads of perfect focus amidst a wide sky of muddled stars.

Anderson also changed cinematographers for the first time among his feature films, using Mihai Mălaimare, Jr. and shooting entirely on 65 mm. The resulting picture is startlingly precise, trenchant, and deeply beautiful, capturing both the pristine definition of nearly neon-blue Pacific waves as well as the warm, granulated semi-sepia cast of Quell’s department store family portraits.

Anderson also changed cinematographers for the first time among his feature films, using Mihai Mălaimare, Jr. and shooting entirely on 65 mm. The resulting picture is startlingly precise, trenchant, and deeply beautiful, capturing both the pristine definition of nearly neon-blue Pacific waves as well as the warm, granulated semi-sepia cast of Quell’s department store family portraits.

This meticulous framing and imagery is equaled by lethally honed dialogue that the actors must have relished. Says Master upon meeting Quell: “I am a writer, a doctor, a nuclear physicist and a theoretical philosopher. But above all, I am a man, a hopelessly inquisitive man, just like you.” It’s stilted in a way, running up almost uncomfortably into stylized intimacy. But those long takes and the camera’s quiet comfort inject an irrepressible rawness and realism that is breathtaking in any context: a steadicam panning through a department store as two well-dressed men fight like wounded birds, or rattling through a dark and claustrophobic clapboard hallway before bursting into a fallow field and sprinting out towards dusk.

These intense passages focus predominantly on Quell, first in his lonely misery and then on the consequences of his thralldom to Master. This leaves the film’s other characters spinning slowly in small eddies of their own, peripheral to the central whirlpool that leads down into indefinite depths. Being so focused and yet so technically unresolved is one of ‘The Master’s challenges. Perhaps this a problem for some, but at least it is a deliberate one. Like Quell pacing doggedly from wall to window, ‘The Master’ is vividly committed to its course, even if that course never seems to land anywhere else than where it started—on a painfully bright beach and Quell alone with his woman made of sand.

These intense passages focus predominantly on Quell, first in his lonely misery and then on the consequences of his thralldom to Master. This leaves the film’s other characters spinning slowly in small eddies of their own, peripheral to the central whirlpool that leads down into indefinite depths. Being so focused and yet so technically unresolved is one of ‘The Master’s challenges. Perhaps this a problem for some, but at least it is a deliberate one. Like Quell pacing doggedly from wall to window, ‘The Master’ is vividly committed to its course, even if that course never seems to land anywhere else than where it started—on a painfully bright beach and Quell alone with his woman made of sand.

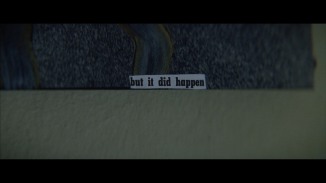

This emptiness may leave some troubled, confused, or merely disinterested. And the film does indeed lack for a universal truth or central dogma to grasp like that so fervently espoused by its Master. But Anderson’s plots are rarely linear and clear in their intent. To experience them is enough. No prescribed lesson need be learned to feel as though something significant has occurred. Anderson, like his Master, shows us an open hand, clenches it so tightly as to make us believe he is holding onto everything, and then opens it again, revealing nothing. And we are kept taut, riveted by his commitment and inspired by his vividness, yet still afforded the slack to seize hold of our own passions, our own struggles, and then release them. Alas, as with Hoffman, some can never let go.