HAVE WE SEEN A BETTER DIRECTOR for dialogue than Sidney Lumet? Not for pithy one-liners or noir-style ratatat, but rather the realistic, extemporaneous flow of human interaction. The kind of patter that makes us forget that these lines have been spoken before, rehearsed, memorized, regurgitated. To watch actors in a Lumet film is to watch them discover each other and themselves, maybe not for the first time, but always anew. ‘Dog Day Afternoon’ (along with the watershed ‘Network’ that came the year after) positively radiates this realism, achieving a nearly documentarian dynamic between actors who bicker, wave guns, huddle together, and sweat profusely through a single late summer night. This eschewal of stylization is especially remarkable for two reasons: firstly, that 90% of the film transpires on an impromptu stage: a held-up bank, spotlighted by police vehicles, transfixed by media cameras, and thronged by a public audience eager to be the comic relief in this drama. Secondly, that ‘Dog Day Afternoon’ is a true story, and films so inspired are often far too self-aware to look anything but stylized.

HAVE WE SEEN A BETTER DIRECTOR for dialogue than Sidney Lumet? Not for pithy one-liners or noir-style ratatat, but rather the realistic, extemporaneous flow of human interaction. The kind of patter that makes us forget that these lines have been spoken before, rehearsed, memorized, regurgitated. To watch actors in a Lumet film is to watch them discover each other and themselves, maybe not for the first time, but always anew. ‘Dog Day Afternoon’ (along with the watershed ‘Network’ that came the year after) positively radiates this realism, achieving a nearly documentarian dynamic between actors who bicker, wave guns, huddle together, and sweat profusely through a single late summer night. This eschewal of stylization is especially remarkable for two reasons: firstly, that 90% of the film transpires on an impromptu stage: a held-up bank, spotlighted by police vehicles, transfixed by media cameras, and thronged by a public audience eager to be the comic relief in this drama. Secondly, that ‘Dog Day Afternoon’ is a true story, and films so inspired are often far too self-aware to look anything but stylized.

We must also acknowledge the flexibility of screenwriter Frank Pierson, who collaborated with Lumet to tape actors’ improve sessions based on his original dialogue and then rewrite scenes to incorporate their spontaneous language, creating a feedback loop that invigorates the written word while also cleaving closer to the actors’ own identities. Contrastingly, the look of the picture is highly particular, reflecting the televised nature of this crisis as it played out on a national stage. Thus the smooth editing and camerawork that retain the elegance and deliberate flow often missing from documentary-style dramas such as ‘The French Connection’. In that film, director William Friedkin didn’t even block out the scenes with his cameramen, forcing them to improvise as they tracked action they’d never been allowed to rehearse. Quite opposite from that on-location cinema verite is Lumet’s picture, occupied almost completely by one meticulously controlled set and explored through Victor Kemper’s long-tracking camera. As night falls and the robbers become hostages themselves, the camera begins to penetrate the walls that separate the factions within the bank, placing the audience in the center of their tableaus as if we were an overlooked hostage crouched beneath a desk.

Even as events in the bank are floodlit from the outdoors in a surreal glow, the actors on screen exist communally in one claustrophobic space that defies planar separation—hostages right, bank robbers left. But once outside, the dynamic is completely reversed, as we watch the action unfold from diametrically opposed perspectives. Over Sonny’s shoulder, we peer out at a hundred pointed gun barrels, as many camera lenses, and the imploring bluster of Detective Moretti (Charles Durning, always authentic). From the other side of the street, we join the media fixed upon Sonny as he paces back and forth against the whitewashed backdrop of the bank, gesticulating wildly by his lonesome, shouting ‘Attica!’, and discovering his passionate desire to be seen, heard, and even to be caught.

Thus Sonny becomes our antihero, played inimitably by Al Pacino in perhaps his last major role before becoming something of a self-caricature. Here, he is typically explosive, confrontational, and passionate, but also vulnerable and deeply conflicted. He manages to seem younger than in either of the ‘Godfather’ pictures made earlier in the 70s and sheds all the gravitas of Michael Corleone in the process. It is a complete—and rather pitiful—transformation that dominates the film in a way quite opposite to Pacino’s habit.

As the crumpled secrets of Sonny’s life are laid out before the camera, the film’s second half could easily have dipped into farce (or satire, more accurately). It does teeter on the brink once, unnecessarily, when we meet Sonny’s clinging wife (mother of his children), and then again, quite necessarily, upon encountering his other wife, Leon, the semi-lucid male psych patient awaiting a sex change. Sonny claims to love both but can understand neither, much less treat them well. In fact, it is towards the characters he knows least that he becomes most polite. Yes, we might say he is caretaker of Sal (John Cazale), his half-Lenny co-conspirator, but Sonny becomes implicit in Sal’s death and thus is rather a poor friend in the end. Yet when it came to throwing hostages’ bodies out the door, we never really believed he’d do it; the Sonny that allows every teller access to the bathroom, orders them food, and releases ailing hostages is much more genuine. We might laugh at the irony when early on, wielding a rifle half his size, he professes to be Catholic and thus not inclined to hurt anyone, but his conduct, however bizarrely, does not much belie his claim.

Sonny’s brief encounter with his mother, nagging and sentimental, is an unfortunate pastiche that does the film its prime injustice. The pressures Sonny feels from the outside world are made much more tangible, and he more empathetic, through the extraordinary phone conversation he shares with Leon. Intercut by necessity, this sequence still manages an intimacy and dancing delicacy rare even between characters face to face, much less those in a more familiar heterosexual context. Both men are shot quite tightly, closed in on themselves (a hand clasping shut a bathrobe; an arm slung over the forehead), and though they are but a street apart, unmoving, we feel the chasm yawning ever wider between them.

In a film that opens with two faces we recognize from gangster stardom and heavy weapons brandished wildly, only two triggers are pulled. And in a film consumed by one man’s crumbling existence and inevitable failure, a great deal of humor can be found. ‘Dog Day Afternoon’ is not an action flick, nor only a drama, nor any other single style of film. It is life, which is action and inaction, failure and triumph, drama and comedy, all spun together inextricably. Most directors choose one or two of these passions, finding it too great a challenge to encapsulate the complete human condition in two hours. Lumet succeeds. But he succeeds not in encapsulation, which by necessity confines and encloses; rather, he highlights, leaving the context there for us to fill in as we will—as unconsciously, as naturally, as we do in life.

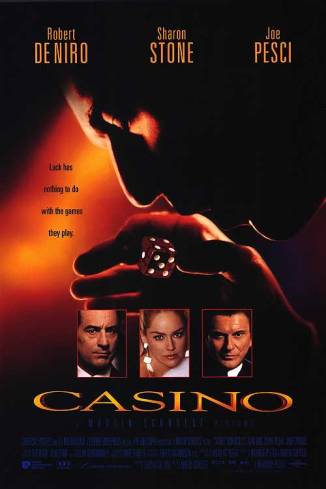

‘CASINO’ IN BRIEF: 90 minutes spent on a labyrinthine (and even somewhat nuanced) buildup of a far-ranging criminal empire followed by 90 minutes of personal disasters. Altogether that makes three hours of bad things happening to people we don’t like. It’s a kitchen-sink approach to filmmaking, with ‘Sunset Boulevard’-style plot arc and narration; not one but two (wait, make it three) characters with voiceovers; freeze frames; slow-motion; dimmers and highlights; subtitles; and a virtually omnipresent pop music bed that dictated the audience’s moods at every turn. Only when characters were completely in collapse, shouting too loudly to appreciate Scorsese’s topical song selection, does the music stop. Like oases, those open spaces beneath the dialogue are welcome moments of respite no matter the scene (e.g. whichever drug-fueled tirade Sharon Stone might be unleashing on a long-suffering Robert De Niro).

‘CASINO’ IN BRIEF: 90 minutes spent on a labyrinthine (and even somewhat nuanced) buildup of a far-ranging criminal empire followed by 90 minutes of personal disasters. Altogether that makes three hours of bad things happening to people we don’t like. It’s a kitchen-sink approach to filmmaking, with ‘Sunset Boulevard’-style plot arc and narration; not one but two (wait, make it three) characters with voiceovers; freeze frames; slow-motion; dimmers and highlights; subtitles; and a virtually omnipresent pop music bed that dictated the audience’s moods at every turn. Only when characters were completely in collapse, shouting too loudly to appreciate Scorsese’s topical song selection, does the music stop. Like oases, those open spaces beneath the dialogue are welcome moments of respite no matter the scene (e.g. whichever drug-fueled tirade Sharon Stone might be unleashing on a long-suffering Robert De Niro). If it weren’t so constantly self-congratulatory, ‘Casino’ might be enjoyable without caveat, as it is fundamentally sound as both a gangster film and a rise-and-fall memoir. But Scorsese simply has too much fun with his own have-it-both-ways take on Italian mobsters—Romantic and brutalized—so a story that would have been stretched at two hours somehow sprawls into three. Most of Scorcese’s big pictures handle themes akin to ‘Casino’s, but none spends as much time setting up a payoff that is hardly rewarding. ‘The Departed’ is the only film for which he has won an Oscar for Best Director, perhaps because it broke out of this expository rut and allowed its characters to define themselves through their interactions instead of the aggrandizing, rather detached monologues used here (and in ‘Goodfellas’).

If it weren’t so constantly self-congratulatory, ‘Casino’ might be enjoyable without caveat, as it is fundamentally sound as both a gangster film and a rise-and-fall memoir. But Scorsese simply has too much fun with his own have-it-both-ways take on Italian mobsters—Romantic and brutalized—so a story that would have been stretched at two hours somehow sprawls into three. Most of Scorcese’s big pictures handle themes akin to ‘Casino’s, but none spends as much time setting up a payoff that is hardly rewarding. ‘The Departed’ is the only film for which he has won an Oscar for Best Director, perhaps because it broke out of this expository rut and allowed its characters to define themselves through their interactions instead of the aggrandizing, rather detached monologues used here (and in ‘Goodfellas’).

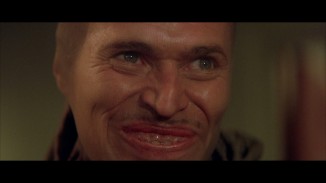

LIKE MOST FINCHER PICTURES, this English-language adaptation of ‘Män som hatar kvinnor’ is an intellectual, composed, and dark (literally and figuratively) gauntlet of buried revelations, brooding emptiness, and periodic explosions of articulated violence. In all these respects it mirrors the Swedish-language original, directed by the Danish Niels Opleve, which is shorter by just 8 minutes. It is clear that Fincher was attentive to the original film, referencing its qualities in his commentary, but he is equally dedicated to presenting his own interpretation of Stieg Larsson’s grim novel and equally separate in focusing on his own cast instead of constantly referencing the novel or the first film. Indeed, it is difficult to say something original about a character who has already been broadly and famously explored twice within the past decade, but Fincher’s angle on the tale and the competency of his cast make this version worth experiencing.

LIKE MOST FINCHER PICTURES, this English-language adaptation of ‘Män som hatar kvinnor’ is an intellectual, composed, and dark (literally and figuratively) gauntlet of buried revelations, brooding emptiness, and periodic explosions of articulated violence. In all these respects it mirrors the Swedish-language original, directed by the Danish Niels Opleve, which is shorter by just 8 minutes. It is clear that Fincher was attentive to the original film, referencing its qualities in his commentary, but he is equally dedicated to presenting his own interpretation of Stieg Larsson’s grim novel and equally separate in focusing on his own cast instead of constantly referencing the novel or the first film. Indeed, it is difficult to say something original about a character who has already been broadly and famously explored twice within the past decade, but Fincher’s angle on the tale and the competency of his cast make this version worth experiencing.

HAVE WE SEEN A BETTER DIRECTOR for dialogue than Sidney Lumet? Not for pithy one-liners or noir-style ratatat, but rather the realistic, extemporaneous flow of human interaction. The kind of patter that makes us forget that these lines have been spoken before, rehearsed, memorized, regurgitated. To watch actors in a Lumet film is to watch them discover each other and themselves, maybe not for the first time, but always anew. ‘Dog Day Afternoon’ (along with the watershed ‘Network’ that came the year after) positively radiates this realism, achieving a nearly documentarian dynamic between actors who bicker, wave guns, huddle together, and sweat profusely through a single late summer night. This eschewal of stylization is especially remarkable for two reasons: firstly, that 90% of the film transpires on an impromptu stage: a held-up bank, spotlighted by police vehicles, transfixed by media cameras, and thronged by a public audience eager to be the comic relief in this drama. Secondly, that ‘Dog Day Afternoon’ is a true story, and films so inspired are often far too self-aware to look anything but stylized.

HAVE WE SEEN A BETTER DIRECTOR for dialogue than Sidney Lumet? Not for pithy one-liners or noir-style ratatat, but rather the realistic, extemporaneous flow of human interaction. The kind of patter that makes us forget that these lines have been spoken before, rehearsed, memorized, regurgitated. To watch actors in a Lumet film is to watch them discover each other and themselves, maybe not for the first time, but always anew. ‘Dog Day Afternoon’ (along with the watershed ‘Network’ that came the year after) positively radiates this realism, achieving a nearly documentarian dynamic between actors who bicker, wave guns, huddle together, and sweat profusely through a single late summer night. This eschewal of stylization is especially remarkable for two reasons: firstly, that 90% of the film transpires on an impromptu stage: a held-up bank, spotlighted by police vehicles, transfixed by media cameras, and thronged by a public audience eager to be the comic relief in this drama. Secondly, that ‘Dog Day Afternoon’ is a true story, and films so inspired are often far too self-aware to look anything but stylized.