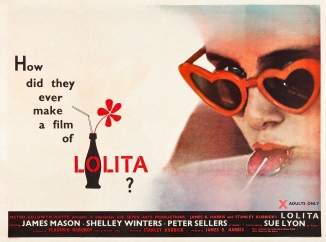

“HOW DID THEY ever make a film of Lolita?” goes the tagline. A reasonable question, given that its narrator, Humbert Humbert, is narcissistic, mildly sociopathic, snootily cosmopolitan, showily overeducated, hopelessly European, and happens also to be an inveterate pedophile. Consider also that its year of release (1962) came a mere two years after ‘Psycho’ shocked the censors by depicting an adult couple of philanders in the same bedroom. Though the prurient details of ‘Lolita’s taboo relationship were never explicitly shown, the very fact that a pubescent girl and her 50-something lover stepfather might be the subject of a film showed that the primrose walls of the Production Code were tumbling swiftly indeed.

“HOW DID THEY ever make a film of Lolita?” goes the tagline. A reasonable question, given that its narrator, Humbert Humbert, is narcissistic, mildly sociopathic, snootily cosmopolitan, showily overeducated, hopelessly European, and happens also to be an inveterate pedophile. Consider also that its year of release (1962) came a mere two years after ‘Psycho’ shocked the censors by depicting an adult couple of philanders in the same bedroom. Though the prurient details of ‘Lolita’s taboo relationship were never explicitly shown, the very fact that a pubescent girl and her 50-something lover stepfather might be the subject of a film showed that the primrose walls of the Production Code were tumbling swiftly indeed.

But a better question, and one perhaps more relevant in retrospect, is “How did they ever make a comedy of Lolita?” In contemporary cinema, themes of incest and pedophilia are increasingly addressed, but when are these modern films ever given a comic twist? That Kubrick and company approached the topic from such a wry perspective and with such a flip air of tra-la playfulness almost makes them complicit in Humbert’s lechery. Such a tack seems almost unfathomable today. Or maybe, as Polanski might have said of that time, ‘Everybody was doing it.’

But a better question, and one perhaps more relevant in retrospect, is “How did they ever make a comedy of Lolita?” In contemporary cinema, themes of incest and pedophilia are increasingly addressed, but when are these modern films ever given a comic twist? That Kubrick and company approached the topic from such a wry perspective and with such a flip air of tra-la playfulness almost makes them complicit in Humbert’s lechery. Such a tack seems almost unfathomable today. Or maybe, as Polanski might have said of that time, ‘Everybody was doing it.’

The film does have its moments of drama, to be sure, but the best indicator of a picture’s tenor is often its music, and here ‘Lolita’ is unabashedly breezy. Returning consistently to a ditty of Dadaist simplicity, it makes childish mockery of Lolita’s torn veil of innocence and Humbert’s increasingly maudlin attempts to preserve her in his idealized private garden. Conversely, the book did also have its humorous side: Nabokov writes with such a joie-de-vivre and Humbert possesses such coruscating wit that it’s impossible not to enjoy ‘Lolita’ as a page-turner or even whimsical travelogue at times. Yet Humbert remains a deeply tragic character, and once that glib sheen of verbosity and ego is prized away we must confront the ragged threads of suburban desperation. Making a similar film would admittedly have been difficult; it’s hard to see how this jarring blend of drama and black comedy was any easier a sell.

The film does have its moments of drama, to be sure, but the best indicator of a picture’s tenor is often its music, and here ‘Lolita’ is unabashedly breezy. Returning consistently to a ditty of Dadaist simplicity, it makes childish mockery of Lolita’s torn veil of innocence and Humbert’s increasingly maudlin attempts to preserve her in his idealized private garden. Conversely, the book did also have its humorous side: Nabokov writes with such a joie-de-vivre and Humbert possesses such coruscating wit that it’s impossible not to enjoy ‘Lolita’ as a page-turner or even whimsical travelogue at times. Yet Humbert remains a deeply tragic character, and once that glib sheen of verbosity and ego is prized away we must confront the ragged threads of suburban desperation. Making a similar film would admittedly have been difficult; it’s hard to see how this jarring blend of drama and black comedy was any easier a sell.

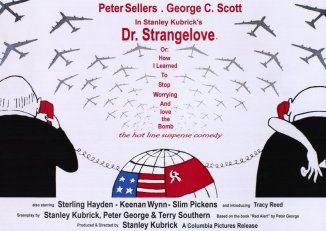

At least, that is, before Peter Sellers arrived. His chameleonic brilliance takes charge of the film from its opening scene and guides the audience through a fraught emotional minefield. By revealing his bête noire at the opening, Kubrick inverts the representation of Quilty’s novelized form, which was hidden till the very end. Instead of that lurking paranoia, in the film we’re given full insight into a parade of absurdity that, while less haunting and sympathetic to Humbert, is the more natural play for the film’s comic tone and the best use of Sellers’s skills. Indeed, one can see how Sellers’s multiple characterizations and outsized impressions in ‘Lolita’ inspired a repeat in 1964’s ‘Dr. Strangelove’. Paralleling Roman Epicureanism (replete with accidental toga), disaffected contemporary celebrity, hokey aw-shucks everymen, and a walking Freudian punchline in turn, the farcical Sellers is the perfect antiphony to Mason’s cultured coolness.

Another alteration more ill-advised is the cutting to Humbert’s frequent asides to the reader, here pared down to a scant handful of voiceovers that nudge the story occasionally without revealing his character’s complex history. Lacking that insight, we come to empathize with him for his natural charm as an adult, as well as by perceiving Lolita increasingly as his daughter while overlooking what happens in those motels once the lights (and camera) switch off. Nabokov had a harder sell in the book: an explicitly perverse mind and its sordid past made into our hero, however defective. As it happens, Nabokov was credited as the screenwriter for this film, but his version was evidently not much utilized. Kubrick, for whatever reason, preferred to focus less on Humbert’s more erudite qualities and more on his piteous fall into jealously and weakness.

And in this regard Mason is astounding—one of the few ever able to embody polished, high-society urbanity just as naturally as wide-eyed, bestial mania. When a late-night phone call from his specter, Quilty, awakes him in a rented bungalow where he has fallen ill while Lolita is hospitalized, the swollen, bug-eyed, hoary face that emerges from those blankets is that of a deranged caveman, not a professor of French literature. His age for this film was also perfect. Entering his 50s, he was still a virile, attractive, and confident man, but one could also see the jowls beginning to sag, the crows’ feet deepening about his eyes, and a faint weariness about his proud shoulders that lent him the credence to sob his loss away in Lolita’s shabby home while she watched, married, pregnant, aloof. Sue Lyon, meanwhile, plays Lolita with all the natural ease of a beautiful girl who knows it and wields that beauty well, but still is dulcet in youth and not jaded into a malicious or petty adulthood. That task is left to her mother, Charlotte, the third corner of this triangle. Played by a perfectly grasping Shelly Winters, Charlotte’s insecurities push an already delicate balance of power past its breaking point, propelling the story out of its long preamble. Her character’s departure is rather abrupt in the novel—Nabokov is merciless—and similarly swift in the film, though Charlotte’s trimmed role and an overall lighter tone undercut the episode’s severity. Much of ‘Lolita’ moves in this way, in fact: rich ingredients poised to excel, but undermined a little here and a little there by its own machinations until its falls for good from the top shelf of Kubrick’s works.

Strange as it seems, then, it’s the script that ultimately makes ‘Lolita’ less than a masterpiece. What else might it be? With a visionary director, exceptional cast, competent editing, and no question of production value, few major elements are left to blame beside the script. Perhaps ‘blame’ is a harsh word to use: ‘Lolita’ is still a salacious delight, cagily experimental, prickly with controversy, and utterly unapologetic. But whereas the book augmented these qualities them with singular perspective and prose that laughed even as it bled, Kubrick’s filmed adaptation seems to gloss over the deepest depths. Perhaps, then, this is how they made a comedy of ‘Lolita’—by ignoring the primal impetus of the beast they’ve caged and are poking for a lark.