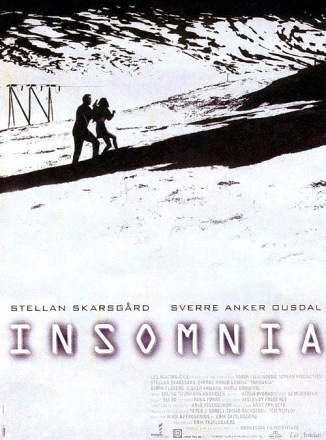

BEFORE STIEG LARSSON (or more ironically, his death) introduced the world to Lisbeth Salander, Scandinavian crime drama had already developed a durable and distinctive model spanning cinema, television, and text. Its plots explored the tacit tension between progressive societies and provincial prejudice, half-hearted protagonists with misanthropic streaks, and a melancholic pallor unique to the lands of the midnight sun. Larsson’s ‘Millennium’ books and their filmed adaptations have become the most recognized of these stories, but their very fame also decouples them from the unheroic anonymity the genre prefers. A better illustration might be Erik Skjoldbjærg’s ‘Insomnia’ from 1997, which follows Jonas Engström (Stellan Skarsgård), a disgraced Swedish detective, to a remote Norwegian town north of the Arctic Circle to solve the murder of a teenage girl. It’s an unremarkable premise, assuredly among the oldest in crime fiction. But if one cliché may allow another, ‘the devil is in the details’ and in ‘Insomnia’ they are sinister indeed.

BEFORE STIEG LARSSON (or more ironically, his death) introduced the world to Lisbeth Salander, Scandinavian crime drama had already developed a durable and distinctive model spanning cinema, television, and text. Its plots explored the tacit tension between progressive societies and provincial prejudice, half-hearted protagonists with misanthropic streaks, and a melancholic pallor unique to the lands of the midnight sun. Larsson’s ‘Millennium’ books and their filmed adaptations have become the most recognized of these stories, but their very fame also decouples them from the unheroic anonymity the genre prefers. A better illustration might be Erik Skjoldbjærg’s ‘Insomnia’ from 1997, which follows Jonas Engström (Stellan Skarsgård), a disgraced Swedish detective, to a remote Norwegian town north of the Arctic Circle to solve the murder of a teenage girl. It’s an unremarkable premise, assuredly among the oldest in crime fiction. But if one cliché may allow another, ‘the devil is in the details’ and in ‘Insomnia’ they are sinister indeed.

The film is shot without much glamor, professionally albeit with an apparently limited budget and on-location. The cinematography has a washed-out, documentarian feel starkly enhanced by the super-8 styling of its startling opening sequence. Soon after meeting Engström we feel as though we’re behind the scenes of an episode of ‘Cops’ to intimate and explicit for public broadcast. When the detective arrives to town it is beset by fog and dusky despite the midnight sunlight. He has little knowledge of his new colleagues, the case at hand, or the land itself; the fog seems to shrouds many paths into the future and provides no hints of which to take. Then, in a moment of forgivable confusion, he makes a terrible mistake and his world starts fading into white. Not black. Rather, a perpetual light that slowly sinks him into isolated chambers lacking continuity with the world beyond. Standing in an apartment and looking towards the window, all we see is a blinding brightness that refuses to give way. Engström is locked inside an open cage, in sleepless purgatory. And then ‘Insomnia’ truly begins.

When the detective arrives to town it is beset by fog and dusky despite the midnight sunlight. He has little knowledge of his new colleagues, the case at hand, or the land itself; the fog seems to shrouds many paths into the future and provides no hints of which to take. Then, in a moment of forgivable confusion, he makes a terrible mistake and his world starts fading into white. Not black. Rather, a perpetual light that slowly sinks him into isolated chambers lacking continuity with the world beyond. Standing in an apartment and looking towards the window, all we see is a blinding brightness that refuses to give way. Engström is locked inside an open cage, in sleepless purgatory. And then ‘Insomnia’ truly begins.

The role is perfect for Skarsgård: looming, weary, soft-spoken, yet at times brutally forceful, we believe both his temerity and his ambivalence. In the land of the midnight sun he is a perpetual shadow. His relationships with other characters are quite vaguely sketched, but absolutely meticulous blocking gives the attentive viewer all he needs to know. In groups of two or three, characters subtly orbit through three-quarters shot to reflect the constantly changing power dynamics. Sometimes they enter the frame at an unexpected angle or at a strange interval, as if the film was jump-cut and we blinked a second too long. Or, like Engström, we fell prey to a sleepless exhaustion. The dialogue, meanwhile, is straightforward and largely procedural—only by watching the visual cues (how the camera disguises a face, how a character meets or avoids another’s eyes) can we fully appreciate the forces at play. For Engström is not one to betray his intentions, not least after he has become complicit in the very case he’s investigating.

In this sense it is hard to classify this film as a character study, since it does not sufficiently explore or reveal Engström’s character. At the beginning we get hints of his background—disgrace in Sweden, virtual banishment to the boondocks—and at the end his future remains unclear. A minimalist score by Biosphere, largely ambient/electronic, also gives us precious few cues. It is not the director’s intent, nor that of his co-screenwriter Nikolaj Frobenius, for us to reflect on Engström as an archetype or dissect him as a specimen. But neither is he a cipher, simply channeling his environment without coloring it. To the contrary, his flaws and failures directly cause everything in ‘Insomnia’ aside from the murder that began it. The story simply exists.

In this sense it is hard to classify this film as a character study, since it does not sufficiently explore or reveal Engström’s character. At the beginning we get hints of his background—disgrace in Sweden, virtual banishment to the boondocks—and at the end his future remains unclear. A minimalist score by Biosphere, largely ambient/electronic, also gives us precious few cues. It is not the director’s intent, nor that of his co-screenwriter Nikolaj Frobenius, for us to reflect on Engström as an archetype or dissect him as a specimen. But neither is he a cipher, simply channeling his environment without coloring it. To the contrary, his flaws and failures directly cause everything in ‘Insomnia’ aside from the murder that began it. The story simply exists.

Only once the film is through do we realize what a tightrope it has walked, between gratuity and obfuscation, obsession and apathy, unavoidable concrete evidence and pure fabrication. And though Engström’s life is weary, callous, unsympathetic, and locked in a downward spiral, the viewer does not feel belabored or tortured by the viewing. Skjoldbjærg is not concerned with shock and awe, nor is his main character a long-suffering masochist whose soul-wrenching distress is visited upon his audience with mordant glee (looking at you, Darren Aronofksy). Neither are we left cold by the proceedings—we feel alarm and dismay, some revulsion and exhaustion all—but there remains a foundation of sobriety and somberness that allows us to engage the narrative as it if were a vivid police report and not an abusive rite of passage. The film ends with a long cut of Engström riding away in the back of a car, caught but not captured, with his deadened eyes looking almost directly into the camera as if to ask, ‘who are you to judge?’

A 2002 remake by Christopher Nolan starred Al Pacino and Robin Williams. (Amidst decades of ebullient joy, in that one year Williams unleashed a lifetime of villainy in ‘Death to Smoochy’ and ‘One Hour Photo’ besides.) Predictably, it spent too much of its energies on the mind games of its characters and too little on the environment that birthed them. The difference is critical: people end, places don’t. And this is the sober center of the Scandinavian model, where the petty lunacy of man plays out across indifferent landscapes. Our greed may mar their surfaces over the years, but their influence on us is far more final. Their indefinite expanse defies the closure human stories crave, and they outlast us. Sleepless.

A 2002 remake by Christopher Nolan starred Al Pacino and Robin Williams. (Amidst decades of ebullient joy, in that one year Williams unleashed a lifetime of villainy in ‘Death to Smoochy’ and ‘One Hour Photo’ besides.) Predictably, it spent too much of its energies on the mind games of its characters and too little on the environment that birthed them. The difference is critical: people end, places don’t. And this is the sober center of the Scandinavian model, where the petty lunacy of man plays out across indifferent landscapes. Our greed may mar their surfaces over the years, but their influence on us is far more final. Their indefinite expanse defies the closure human stories crave, and they outlast us. Sleepless.

JUSTIFIABLY, CHRISTOPHER NOLAN has become one of the new millennium’s top-flight names in Hollywood. His Batman trilogy redefined the paradigm of superhero films, while others like ‘

JUSTIFIABLY, CHRISTOPHER NOLAN has become one of the new millennium’s top-flight names in Hollywood. His Batman trilogy redefined the paradigm of superhero films, while others like ‘

RELEASED THE SAME YEAR director Christopher Nolan turned 30, ‘Memento’ is that rare transitional film that really succeeds. It features the intimacy of a low-budget film (costing a 50th of his recent ‘The Dark Knight Rises’) as well as the polish and professional treatment of a major studio effort. The core of its small cast is comprised of famous faces—not names—that live in front of the camera with disarming ease. The plot is deliberately tricky, a little attention-seeking in its cleverness, as an ambitious young director (and his writer brother) might be expected to concoct. But it is so tightly knit and draws such an earnest performance from its leading man, Guy Pearce that the audience is soon too caught up in Leonard Shelby’s backwards and forwards life to bother with what’s happening behind the camera lens. Pearce, a fine actor not often in fine films, is heavily tested here, needing to be charismatic without being pitiful and purposeful without the conviction of knowledge. He is sympathetic enough to like, but not so likeable that we can’t suspect him of murder or believe him when he commits it. His unwavering intensity and laissez-faire spontaneity are the two sides of his fraught personality and he flips them expertly.

RELEASED THE SAME YEAR director Christopher Nolan turned 30, ‘Memento’ is that rare transitional film that really succeeds. It features the intimacy of a low-budget film (costing a 50th of his recent ‘The Dark Knight Rises’) as well as the polish and professional treatment of a major studio effort. The core of its small cast is comprised of famous faces—not names—that live in front of the camera with disarming ease. The plot is deliberately tricky, a little attention-seeking in its cleverness, as an ambitious young director (and his writer brother) might be expected to concoct. But it is so tightly knit and draws such an earnest performance from its leading man, Guy Pearce that the audience is soon too caught up in Leonard Shelby’s backwards and forwards life to bother with what’s happening behind the camera lens. Pearce, a fine actor not often in fine films, is heavily tested here, needing to be charismatic without being pitiful and purposeful without the conviction of knowledge. He is sympathetic enough to like, but not so likeable that we can’t suspect him of murder or believe him when he commits it. His unwavering intensity and laissez-faire spontaneity are the two sides of his fraught personality and he flips them expertly.